May We Be So Fortunate

- Peter Chełkowski Sr. & Jr.

- Dec 9, 2024

- 8 min read

Updated: Apr 9

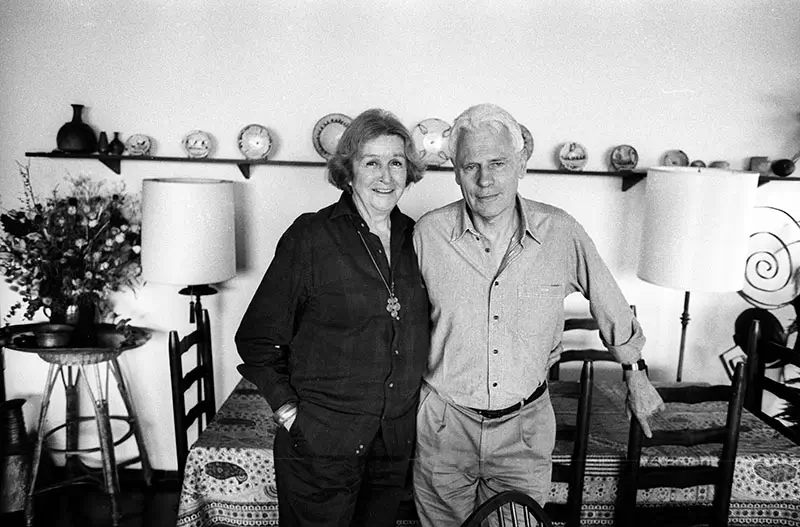

Phot. Jan Hausbrandt

Thank you all for coming. I'm so glad to see many familiar faces. After all, my dad was a New Yorker. He spent 50 glorious years here in this city, longer than anywhere else in his life. And this very church, where we have gathered today, plays a central role in our lives. I was actually christened here in 1969.

It has been uplifting, these last couple of weeks, to read very touching, inspiring messages from his friends, his family and colleagues. My dad was truly a remarkable man.

In his field, he was one of world’s leading scholars on Islamic studies - respected and celebrated globally. He authored and published 12 books, many of them award winning, on a diversity of subjects from cultural criticism through politics and propaganda to mysticism.

In the classroom, he was a beloved professor. He knew how to reach his students. He knew that to make a difference, one had to touch their hearts and minds, and indeed he didn't simply give a lecture but a performance – entertained them and captivated their full attention. Needless to say his students adored him.

His lectures, however, were not limited to the classroom. He hosted 46 episodes of the Sunrise Semester on CBS. This educational series became so popular that his photo graced the cover of The TV Guide, accompanied by the telling headline: “Prof. Peter Chelkowski, I love you”. He became also the go to expert for all things Middle Eastern for the major news outlets: BBC, NBC, CBS, Voice of America, NPR.

I’d say that his unofficial mission in life was to change the way the western man perceives Islam. He fell in love with that still largely strange and mysterious world, and wanted to show people its beauty and wonder.

For his work over five decades he was honored with many awards from the Shah to the President of Poland, and lately by UNESCO a well as the Islamic Republic of Iran. This is his important legacy, and these laurels highlight his great and successful professional career. But they do not make him remarkable.

To me what made my father remarkable, what made him a giant in his impact on us, was the size of his heart. A heart that was filled with kindness and love for everyone – from family, to friends, to complete strangers. He valued everyone he met regardless of race, religion, or economics. He made everyone feel seen and heard and valued.

I can honestly say my Dad made this world a better place. I love what Ehsan, his last teaching assistant at New York University, wrote recently: The lives Peter touched carry forward his spirit, and his scholarship stands as a testament to a mind that sought not only to understand but to connect, to bridge, and to illuminate. Peter’s legacy lives quietly in the questions he encouraged us to ask and in the compassion with which he approached every culture, every story, and every person he encountered.

And so today although it’s hard not to be saddened by his passing, I can’t help but rejoice in the joy and love, compassion and wisdom he brought to us. And I believe he would have liked, maybe even hoped for us to follow in his footsteps: to lead with our hearts.

In the epic tale of Layla and Majnun, one of the greatest love stories ever written, the Romeo and Juliet of the Muslim world, Majnun is lost in the desert, far away from Layla. He yearns to reconnect with her and share his powerful love. So he writes messages to Layla and releases them into the wind with the hope they will ultimately reach her.

My father, I believe, has been sending us these messages his whole life. Messages of Love, of Kindness, of Compassion. May we be so lucky, so fortunate, as to catch them!

Eulogy by Peter Chelkowski Jr.

November 21, St. Stanislaus Kostka Church, East 7th Street, East Village, New York.

Peter Chelkowski

Time Out Memory: Ta’ziyeh, the Total Drama (excerpts)

The dramatic form known as the passion play is often associated exclusively with Western, and specifically, Christian theatrical tradition. One of the most highly developed and powerful examples of this genre is, in fact, the ta'ziyeh -- the passion play of the Shiite Muslims performed in Iran -- which recounts the tragedy of Hussein, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad.(…)

The tragedy reenacts the death of Hussein and his male children and companions in a brutal massacre on the plain of Karbala, (about 60 miles south of modern day Baghdad), in the year 680 AD. Hussein's murder was the outcome of a protracted power struggle for control of the nascent Muslim community following the death of the Prophet Muhammad. Two factions arose with competing views on the leadership selection process for the head of the community, or caliph. The Sunnis believed that the caliph should be elected according to ancient Arabian tradition, while the Shiites advocated that the descendants of the Prophet Muhammad possessed a divine right to authority in both spiritual and temporal matters. Hussein became the head of the Shiites after religio-political opponents assassinated his father and elder brother. His refusal to swear allegiance to Yazid, the Sunni caliph in Damascus, made it necessary for Hussein to seek refuge in Mecca. Eventually with his family and a group of supporters, he set out for Kufa, a city where he had numerous partisans.

On the journey to Kufa, Hussein and his party were ambushed by Yazid's troops and forced to swear an oath of allegiance to the Sunni leader as the price of their freedom. Tradition has it that this took place on the first day of the month of Muharram. For ten days, Hussein's company was cut off from water in the scorching desert of Karbala. Despite the knowledge that his supporters in Kufa had abandoned him after being terrorized by Yazid's army, Hussein refused to take the oath. On the tenth day, after an intense battle, all the male members but one of Hussein's party were savagely killed. Their heads were cut off and taken as trophies to Yazid in Damascus, while the female members of the party were taken hostage. The battle at Karbala and its aftermath precipitated the definitive schism of the Sunni and Shiite Islamic branches.

The slaughter at Karbala came to be considered by the Shiites as the ultimate example of sacrifice, the pinnacle of human suffering. The month of Muharram became the month of mourning, when Shiites all over the world commemorate Hussein's sacrifice in stationary and ambulatory rituals of unequaled intensity. It was from these ritual observances that ta'ziyeh, which literally means to mourn or to console, arose as a dramatic form. (…)

Like Western passion plays, ta'ziyeh dramas were originally performed outdoors at crossroads and other public places where large audiences could gather. Performances later took place in the courtyards of inns and private homes, but eventually unique structures called takiyeh or Husseinyeh were constructed by individual towns for staging of the plays. Community cooperation was encouraged in the building and decoration of the takiyeh whether the funds for the enterprise were provided by a wealthy, public-minded benefactor or by contributions from the citizens of a particular district. The takiyeh varied in seating capacity from intimate structures able to accommodate a few dozen people to large buildings capable of holding 1000 spectators or more.

(…)

In the last 50 years or so, Europeans and Americans have traveled to Asia to experience the bond between actor and audience that is one of the hallmarks of the Eastern dramatic tradition. The most common destinations were India and the Far East, but in the late 1960s, Peter Brook, Jerzy Grotowski, and Tadeusz Kantor discovered ta'ziyeh. Brook, in particular was profoundly impacted by the dramatic possibilities of the Persian form. He explained:

I saw in a remote Iranian village one of the strongest things I have ever seen in theatre: a group of 400 villagers, the entire population of the place, sitting under the tree and passing from roars of laughter to outright sobbing -- although they knew perfectly well the end of the story -- as they saw Hussein in danger of being killed, and then fooling his enemies, and then being martyred. And when he was martyred, the theatre form became truth. (Parabola, 1979)

Brook proved that Iranian dramatic conventions and cultural themes could be effectively transposed to the Western stage with his successful adaptation of a 12th-century mystical tract, The Conference of the Birds, into a theatrical play.

Jerzy Grotowski also borrowed from the ta'ziyeh tradition to fuse dramatic action with ritual as a means of uniting actor and audience. However, his productions for the Laboratory Theater carefully controlled the dynamic between the players and the spectators by imposing limits on space, audience size, and seating placement. ta'ziyeh, in contrast, actively retains a fundamental principle of intimacy without placing any constraints on the size of the performance space or the number of spectators. This is le theatre total.

Goga & Piotr Chełkowski, 2003. Zdjęcia Jan Hausbrandt

Z przedmowy Piotra do wspomnień Wojciecha Chełkowskiego:

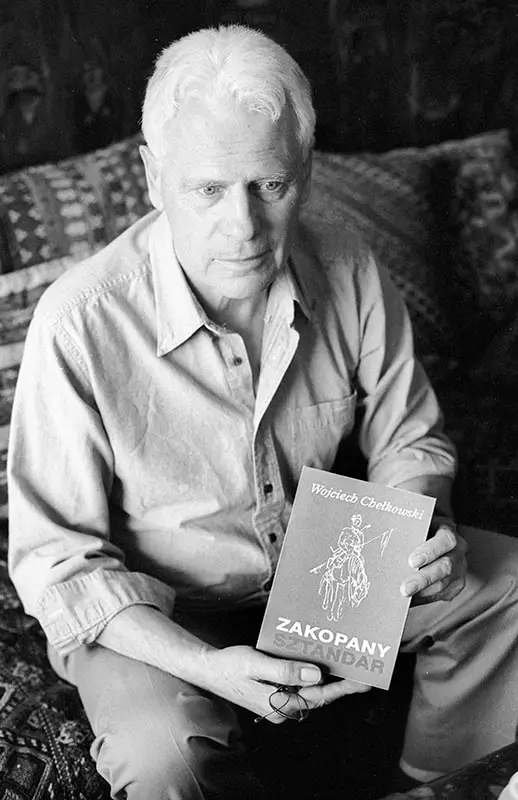

Rękopis tej książki napisany w języku angielskim znalazłem w Irlandii w roku 1984, w rok po śmierci autora, mojego ojca. Zakopany sztandar był pisany parokrotnie: najpierw po polsku jesienią i zimą 1939/40 w Brzozie, w Radomskim, gdzie autor ukrywał się i leczył z ran odniesionych w walkach nad Bzurą i w Puszczy Kampinoskiej. (…)

Wojciech Chełkowski przyjął pseudonim Dersław Dębicki, a swój dom rodzinny, Śmiełów, nazwał w książce Dębno. Pseudonim autora i nazwa domu rodzinnego związane są z tradycją Mickiewiczowską. Śmiełów (Dębno) jest jedynym domem w obecnych granicach Polski, w którym mieszkał Adam Mickiewicz (sierpień, wrzesień 1831 roku). Ślady pobytu poety w Śmiełowie odnajdujemy w wielu opisach przyrody w Panu Tadeuszu. Szczególnie dęby śmiełowskie, które wedle tradycji cieszyły się wielkim zainteresowaniem poety, otaczane były szczególną opieką przez moich dziadków, Józefa i Marię Chełkowskich. Moja babka często recytowała Pana Tadeusza swoim dzieciom, a było ich czternaścioro. W tekście Zakopanego sztandaru autor wspomina, jak jego matka wpajała dzieciom patriotyzm w czasie zaboru pruskiego, często uciekając do Mickiewicza. Imię Dersław przyjął mój ojciec celem uczczenia swojego młodziutkiego brata Dersława Edmunda, który poległ w 1939 roku jako ochotnik.

Nowy Jork, jesień 1994

Rysunki Zygmunta Haupta w książce Zakopany sztandar.

Peter J. Chełkowski (b. in 1933 in Lubliniec, Poland, d. October 21, 2024 in Turin, Italy) was a renowned scholar of Middle Eastern studies, specializing in Persian literature, Iranian culture, and Shiite religious traditions. Born in Lubliniec, Poland, he studied Oriental Philology at the Jagiellonian University and acting in the School of Arts in Kraków. He continued his linguistic studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. He earned a Ph.D. in Persian literature from the University of Tehran in 1968, the first Pole to ever receive a doctorate in Iranian Studies.

The same year Chełkowski arrived in New York, with his wife Goga. He spent much of his career teaching at New York University, where he was known for his engaging lectures and dedication to correcting misconceptions about Islam and Middle Eastern culture. He was one of the founders and a longtime director of The Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies and won Golden Dozen Award for Excellence in Teaching.

His books, exploring Persian art, literature, and religious traditions as well as performing arts and contemporary Iranian culture, include Mirror of the Invisible World: Tales from the Khamseh of Nizami (1975); Ta'ziyeh: Ritual and Drama in Iran (1979), Ideology and Power in the Middle East (co-authored with M. J. Pranger, 1988); Staging a Revolution: The Art of Persuasion in the Islamic Republic of Iran (co-authored with Hamid Dabashi, 1999); Eternal Performance: Taziyeh and Other Shiite Rituals (2010). In 2023, he received the "Plus ratio quam vis" medal from the Jagiellonian University for his contributions to Oriental studies. He also donated his vast personal library to the university’s Department of Iranian Studies.

Chełkowski’s work brought people closer to the richness of Middle Eastern culture, leaving behind a legacy of knowledge and understanding.

Comments