The building occupations at Columbia University in 1968 were a kind of earthquake both for me and for the masses of students and staff at Columbia, and that earthquake reverberated throughout the world. For me it marked a central moment in a transition from being someone who believed in American democracy and thought it would be a vehicle to important changes in the status of Black people and America's relationship with the rest of the world.

I had studied American history in grade school and was an admirer of the leaders of the American Revolution and the Constitution that resulted. Thomas Paine was a particular hero of mine. I felt that the founding document had been improved as a result of the Civil War and the emancipation of the slaves. However, I was fully aware that Black people had been treated unfairly since they were freed. The Civil Rights movement had my full support. The March on Washington and the resulting Voting Right Act in 1965 seemed important steps in taking care of long overdue business. Older classmates of mine from high school went to Birmingham during the brutal police attacks there, and I spent a spring break with a group of fellow students working for a man named Hector Black, who was doing organizing in a poor Black section of Atlanta called Lightning. A young woman visited us and told us the solutions to the problems we were witnessing was socialism. I made fun of her, “You are so young, and you have all the answers. You are a prodigy.” She seemed to me a pretentious fool.

Another moment that was notable on that venture of figuring things out came from being invited to dinner by some rich relatives of mine in Atlanta. They sent a car with a driver to collect me. The driver was an elderly Black man. His arrival in Lightning caused a stir. At least a dozen children came out and were dancing around and shouting in amazement at the black Cadillac. My status tripled in a matter of minutes. The driver assessed the situation and invited me to sit in the front with him. He asked me a lot of questions about my work and always responded by saying, “Hmm.” I realized there were different worlds, and it didn't occur to me then, but eventually the idea grew in my mind that I would have to choose between them.

What made me question democracy was the Vietnam War. John Kennedy, who had founded the Peace Corps, was sending soldiers to this far away country that had been a French colony. I came to see Ho Chi Minh as a founding father, like George Washington, who had defeated the colonial power and now was fighting to free the rest of his country. I remember a talk with some high school friends, and I found myself proclaiming myself a socialist and arguing the U.S. should withdraw all our soldiers from Vietnam. One friend, who became an important literary figure, agreed. On the other hand, the son of the State Department officer told me that I was very naïve.

I entered Columbia in the fall of 1966 and soon after joined the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). This student organization was very different from what it became in 1968. They sponsored a talk by a popular history professor who spoke about whether it would be possible get rid of Johnson and get a Democrat who would seek peace. SDS believed in politics then. That changed dramatically. Soon Mark Rudd became leader as the head of the Action Faction. He was an advocate of direct action. SDS fought against having recruiters from the CIA and went from demonstrations to sit-ins that blocked access. Most students and many faculty supported the idea of keeping recruiters from organizations involved in the war away from the university.

When the 1968 actions came there were six demands. Three had to do with dropping disciplinary measures against students. During the summer of 1967 I did anti-draft work in the community. Along with hundreds of students, I became more and more radical. There was a kind of desperation that was cultural as well as political. Young people had their own music, their own political views, their own understanding about sex and relationships. At Barnard a student named Linda Leclaire was caught living with her boyfriend and faced discipline. Everyone I knew thought this was ridiculous. The year I arrived there had been a panty raid. A mob of students went over to Barnard dorms, and the girls there threw down their underwear. In the year 1967-8 that would have been quite unimaginable.

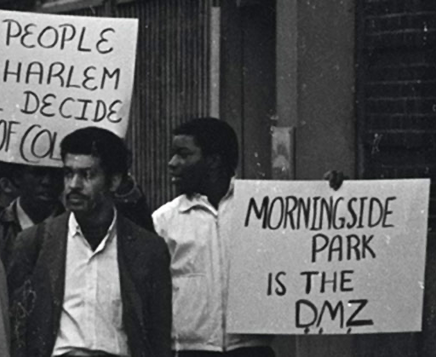

Another set of turning points came in early 1968. In the Tet offensive, the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam caught the Americans off guard. They took many towns and managed to attack the American Embassy in Saigon. Promises that America was winning the war were shown to be lies. Then in April, Martin Luther King was assassinated. The death of the leader of the non-violent Civil Rights Movement had the ironic effect of making many lose faith in non-violence. Younger leaders like H. Rap Brown and Stokely Carmicheal and then the Black Panthers seemed to have a more realistic view of America. I was vacationing in the Virgin Islands when King was killed and heard about the riots everywhere and their brutal suppression. After I came back, S.D.S. issued their six demands: no military research, no new gymnasium in Morningside Park taking land away from Harlem, no discipline of student protesters and amnesty for those already being punished.

The occupation of Hamilton Hall, where most college classes met, started out to be bi-racial. Students presented the six demands and eventually decided not to leave the building. Then the Student Afro-American Society (SAS) members asked the white students to depart. They did so, and went and occupied Low Library, the administration building, breaking into the office of the president, Grayson Kirk Soon Fayerweather and Mathematics were also taken over. I joined the group in Low Library and was asked if I were willing to sacrifice my college education. Not quite convinced it was in jeopardy, I answered, “Of course.”

Photo of occupiers at Low Library, Mathematics Hall, CU campus, April 1968

I am the one on the far left

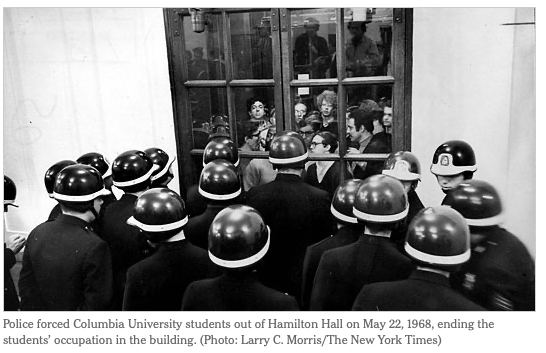

And so ensued a week of communal living, preparing our own food, sleeping in a mass on the floor and having meetings that went on endlessly. At one point the campus conservatives blocked the building and supporters threw food over their heads. It was very exhilarating. It seemed we were finally doing something that matched the terrible things going on in the world, and votes and elections had nothing to do with it. On April 30th the police came and arrested hundreds of students. We were taken down to Center Street and charged with trespassing. What followed was a strike that went on for the rest of the semester.

Pollice clears the Columbia campus, April 30, 1968. Zdj. Steve Ditlea

My faith in American democracy was over. I was cut loose from everything I had learned before. Eventually I came to believe in a version of communism that I learned later owed a lot to anarchism. I saw the world as a battle ground between American imperialism and those in the Third World who wanted to break away and earn independence. I thought the imperialist center would be surrounded by revolutions around the world. Vietnam, Cuba, the Black Revolution in the US all seemed part of something that would bring America down. We were excited by Che Guevara fighting in Africa and Latin America, and saw promise in independence movements in Guinea, Angola, and Mozambique.

In 1970 I went to Cuba with the Venceramos Brigade to cut sugar cane to try to harvest 10 million tons. (We didn't make it.) In Cuba my new faith was shaken a bit. We met a North Korean Brigade whose members seemed to hate us simply because we were American. Maria, from the Cuban Communist Party, attached to my group, wanted to know what girls were wearing in New York, and wondered would anyone sponsor her if she tried to emigrate. A student at a university asked to borrow my razor and didn't return it. Cubans seemed a mixed bag; our minders had an enthusiasm and commitment that ordinary Cubans often lacked.

The police on guard - CU after clearing protesters on April 30, 1968. Barton Silverman. NYT

Another moment of questioning came when I heard that a group of comrades making bombs in a town house in Greenwich Village accidentally blew themselves up. It turned out they had intended to bomb an officers’ club at a base in New Jersey during an event when families would be present.

The beginning of the end of my faith in violent revolution came when a group of us decided to create an affinity group to do urban guerrilla actions. We stole a car and dug a hole in a state park to store guns and dynamite, and then I noticed suddenly there were more and more demonstrations against the bombings ordered by Nixon in Cambodia. Hundreds of thousands of people turned out to demonstrate peacefully, and they had politicians supporting them. They were having an effect. Eventually there were peace talks, eventually American soldiers came home, eventually the NLF conquered Saigon and Vietnam was reunited.

Democracy is slow, messy, imperfect, too dominated by the power of money, but one can use it to accomplish things. Convincing others through talk and debate is more effective, more ethical, than smashing a window or setting off a bomb. My fever, which lasted about three years, finally broke. I am still proud to have been part of the occupation and strike at Columbia. It turned out to be an important event historically and it was an important part of my education. I think it accomplished a lot.

John DeWind, a lifelong New Yorker, holds a Ph.D. in English from Columbia University. For many years he taught literature & creative writing at City College, CUNY, and NYC high schools. He has been a lifelong community organizer and activist, currently involved with the Nostrand Avenue Association. He is now active in an organization called Crown Heights Community Organization which publishes Crown Heights Community News. John lives in Crown Heights with his wife, and they enjoy being devoted grandparents to their two grandchildren.

See also:

• Paul Cronin, ed. A Time to Stir: Columbia '68. (Columbia University Press, 2018.)

• Columbia Spectator archives: http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/digital/collections/cul/texts/ldpd_8603880_000/index.html

• 1968: Columbia in Crisis (exhibition & archival materials):

Comments